Нацистка Русия трябва да бъде разрушена

Моят учител в поезията е Бертолт Брехт.

След като Хитлер идва на власт, Брехт емигрира и започва да пише поезия, чиято пряка цел е поражението на нацистка Германия.

Аз сега не мога да пиша поезия, но нагласата ми е същата. Всеки мой ред има за пряка цел поражението на нацистка Русия.

Никога не съм предполагал, че Русия ще стане нацистка страна в буквалния смисъл на думата. Отчасти поради наивност, отчасти поради интимна детска привързаност към руската литература. Поетът, който пробуди в детските ми години поета в мен, е Пушкин.

Всичко, което знам за Русия отвътре, от 10 години съветско елитно екстериториално училище, поставям на служба на поражението на нацистка Русия.

С всеки мой ред до падането на Путлер ще заявявам:

Нацистка Русия трябва да бъде разрушена.

Не виждам друг начин да спася за себе си моя Пушкин.

Нацистка Русия трябва да бъде разрушена.

Владимир Сабоурин

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Алла Горбунова – Попитаха ме

Петко Дурмана, Дете 39/31

Попитаха ме какво мисля и чувствам за военните действия, които на 24 февруари моята страна започна на територията на друга държава – Украйна. Не знам дали някой се нуждае от тези мои думи. Нека първо бъде спряно кръвопролитието в Украйна, да бъде спряна катастрофата, случваща се докато пиша, и тогава ще може нещо да се каже.

Казаха ми, че за моите колеги – поети и писатели, а също така читатели и издатели в различни страни – ще е важно да чуят какво мисля в момента и как виждам тази ситуация. Боя се, че това е етически капан. Всички думи, които мога да произнеса сега, не са в състояние да спрат случващото се, не могат да превъртят времето назад и да не допуснат случващото се. И като се опитвам да кажа нещо оттук, намирайки се в Русия, аз разбирам, че каквито и искрени чувства да вложа в текста си, нещо в него няма да е наред просто поради самото положение на говорещия. Въпреки това, отговаряйки на молбата ви, ще се опитам да разкажа как аз и хората около мен преживяват случващото се. Понякога разкривените, запъващи се и недостатъчно точни думи все пак са за предпочитане пред мълчанието.

На 24 февруари мнозина мои съотечественици написаха в социалните мрежи, че това е най-страшното утро в живота им. Мои познати ми казваха, че никога в живота си не са изпитвали такъв срам. Аз изпитвах друго доминиращо, всепоглъщащо чувство – скръб. Най-дълбока скръб, в която няма нито сълзи, нито страх, защото и сълзите, и гневът, и дори страхът биха я направила по-лека за понасяне. Чудовищна непоправимост, чувство, че е премината точката, след която няма връщане назад, черта, зад която се отварят вратите на бездната. Вървях по улицата и виждах хората, млади, весели, смеещи се, още не разбиращи какво се случва, какво вече се е случило. И за миг ми се стори, че целият този „обикновен“ живот след случилото се е както когато човек вече са го екзекутирали, отсекли са му главата и тази отсечена глава за кратко още е жива, не разбира какво й се случва.

Има хора, които се стараят да живеят като преди, у които се задействат някакви свои защитни екрани, но много хора в Русия преживяват случващото се като катастрофа без аналог. Нашето общество е разцепено като никога досега. Сред тези, които поддържат действията на властите, има много хора, които са лишени от имунна защита спрямо държавната пропаганда, хора, на които е присъщо онтологическо доверие към властта, към йерархията. Сред хората, обявяващи се срещу военните действия, доколкото мога да преценя, е по-голямата част от творческата интелигенция, младите, студентите. Но всички тези групи не са еднородни. Руското общество в момента не е някакво единно цяло, поддържащо военните действия в Украйна. Струва ми се, че това е едно силно объркано вътре в самото себе си общество, раздробено, разцепено като никога досега, което съвсем не се вписва в шаблоните, което самото то прилага към себе си, разделяйки гражданите си на „зомбираните от официалната пропаганда“, от една страна, и „платените предатели“, от друга. И това общество в момента е за жалост с много висока температура на взаимната омраза.

За много хора събитията от последните седмици изглеждат чудовищни, необясними, ирационални. Аз самата от години чувствам, че това, което се наричаше „нормален живот“, с което изведнъж нещо се случи, отдавна съществува за сметка на това, че на много неща се налагаше да си затваряме очите. И много неща, които на пръв поглед нямат отношение едно към друго, ги виждам като една верига от насилие и болка, която оковава всички нас. И се надявам, че някой ден ще настъпи моментът да прозрем цялата тази оковаваща ни верига от насилие и болка като единно цяло. Но сега най-много от всичко очаквам прекратяването на огъня в Украйна.

Винаги съм обичала Родината си и съм възприемала поезията си като част от руската поетическа традиция и едновременно с това като част от световната поезия. Не знам какво ни очаква. Мнозина мои познати напуснаха страната буквално от днес за утре. Аз не си представям живота извън Русия и ще се мъча да правя възможно най-доброто, на което съм способна, в новите условия. Аз желая Доброто на моята страна и никога няма да се отрека от безкрайно многото, което ме свързва с нея. Но аз разбирам, че има неща, които не могат да бъдат оправдани. И случилото се през последните няколко седмици вече очерта хоризонтите на работата на скръбта и осмислянето за много години и десетилетия напред. Работа, към която никой няма да може да пристъпи докато падат бомбите.

При нас сега са слънчеви мартенски дни. Същото слънце и топящ се сняг като в разрушения Харков. Оттам ми пише забележителен рускоезичен поет, който преди няколко месеца ми прати на съхранение архива си в случай на война между нашите държави. И думите му – отвъд всички бариери – стоплят сърцето ми.

Моя близка приятелка тук, в Русия, много скъп за мен човек, когото чувствам като роден, е психоаналитик и има анализанти в Украйна, правят сесии онлайн, обаждат й се от зоната на бойните действия, за да получат спешна психологическа помощ. Чух и за обратната ситуация: психоаналитикът на моя позната в Русия се намира в Украйна и оттам, понякога от бомбоубежището провежда сесии с нея.

ГОСПОДИ, НЕКА ТОВА БЕЗУМИЕ СПРЕ ЧАС ПО-СКОРО!

И НЕКА ВСИЧКИ СТРАДАЩИ СЕ СДОБИЯТ С ПОМОЩ!

Превод от руски Владимир Сабоурин

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Владимир Сабоурин – Достоевски 200: „Константинопол трябва да бъде наш“

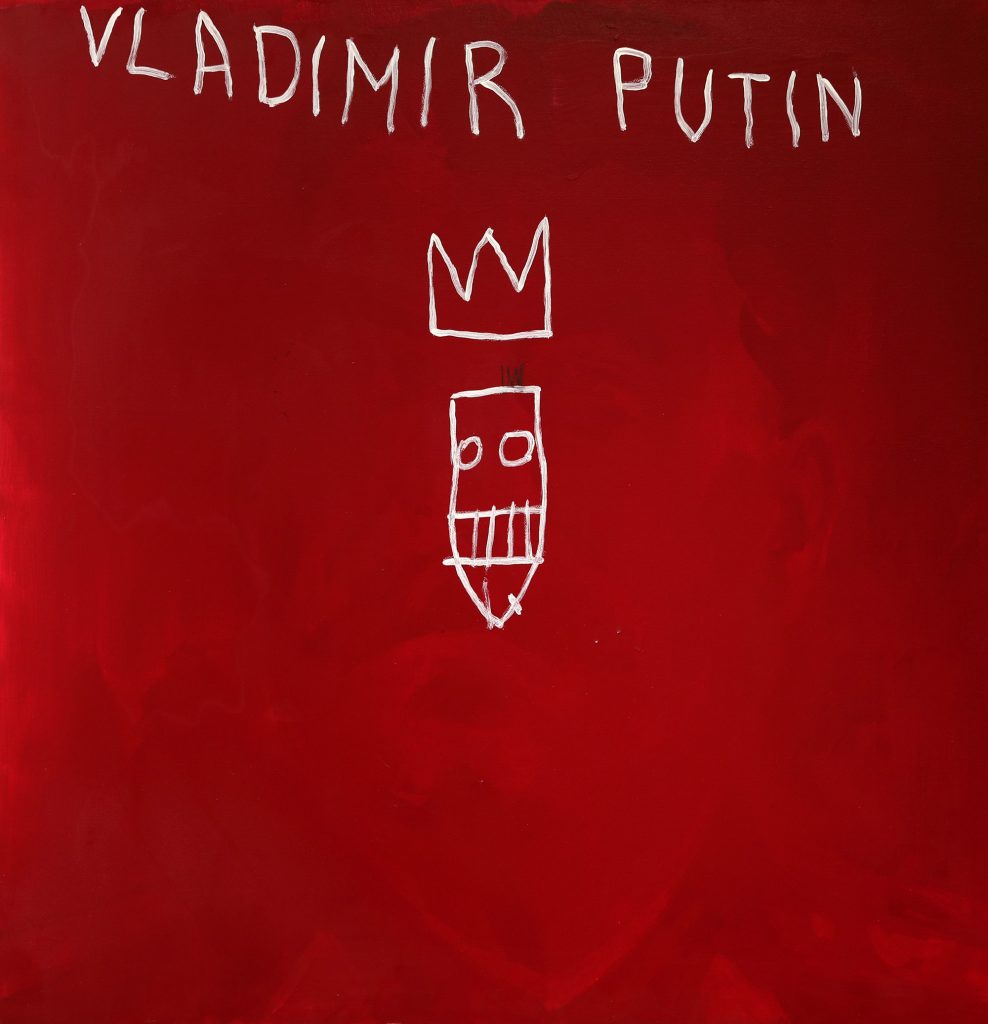

Петко Дурмана, „Двоен портрет #3 – Цар Бомба” (Путин и бомбата)

В кабинета на бащата на Аглая в дома им в Петербург княз Мишкин забелязва познат швейцарски пейзаж, за който е сигурен, че е рисуван от натура – и че е виждал изобразеното място: „това е в кантонът Ури…“[1]. Написаният в Европа Идиот – единственият роман на Достовески, създаден изцяло в чужбина с амбицията да бъде руският Дон Кихот[2] – започва с пристигането на героя в родината и завършва с най-вероятно окончателното му завръщане в Швейцария. В Бесове, започнат в Германия и завършен в Русия, по този обратен път ще поеме губернаторът с немско име и произход, който след нощния пожар в поверения му град окончателно ще е готов за „онова известно специално заведение в Швейцария, където, казват, сега събирал нови сили“ (БЫ Х, 337). Ставрогин – „гражданинът на кантона Ури“ – от своя страна, няма да успее да замине за Ури. Както заминалият, така и останалият, както обладаният от зли духове, така и юродивият, както съзаклятникът, така и психически болният, както революционерът, така и двойникът му самозванец, както самоубиецът, така и конвертитът, както самопревъзмогналият се, така и осъденият на смърт, както писателят, така и престъпникът, както левият радикал, така и консервативният революционер имат в крайна сметка една родина. Рефлексията е всъщност носталгия по тази родина, нагон да сме навсякъде у дома, в авторитарната родина. За княз Мишкин левият радикализъм (и в по по-общ план обръщането на Запад) се корени „в духовната болка, в духовната жажда, в копнежа по […] твърдия бряг, по родината“[3]. Евгени Павлович Радомски, един от неуспешните годеници на Аглая (какъвто е и руският княз с оксиморонно име[4]) и последният приятел, който ще се погрижи за връщането на пациента в Швейцария, малко преди катастрофата ще му каже: „Вие, юношата, жадувахте в Швейцария за родината, стремяхте се към Русия като към неведома, но обетована страна; прочетохте много книги за нея, сами по себе си може би превъзходни, но вредни за вас“.[5] Последната такава прочетена книга би могла да бъде Transhumanism Inc. на Виктор Пелевин. В новия роман на Пелевин откриваме следната кратка история на Русия, представена от гимназиален преподавател от посткарбоновата епоха. „[И]сторията на Русия – така се наричаше преди Добрата Държава – е особено горчива… Това навярно е единствената страна, чийто център на тежест през цялото време е лежал извън пределите й. При всяко положение в културен и духовен смисъл. […]/ Какво е представлявала историята на Добросуд [абревиатура на „Доброе Государство“, б. м., В. С.] на бързо превъртане? Садомазохистична любовна връзка с доислямска Европа./ Строиш Северната Палмира (точно са избрали думичката, всеки тартарен ще го потвърди) – а защо? Напук на интелигентните шведи, за да почнат да те уважават във френския кралски двор… И тогава се почнало: помагаш на Европа да решава династичните въпроси и да дели колониите; въплъщаваш прогресивните учения от немските бирарии и френските университети; градиш Червената Утопия, надявайки се на измислената от немците световна революция – за да се отбраняваш с последни сили пак от техните слънчеви ликвидатори на амфетамини, а като ги отблъснеш с цената на чудовищна кръв, да продадеш опръсканата с нея империя за старо желязо, за да почнеш строителството на нова, близка й по дух, но десет пъти по-слаба, и все от същите кабинети…“[6] В предкарбоновата Империя, предупреждавайки за опасността от идещата Червена Империя, друг руски писател, създал идеалния читател, жадуващ и четящ в Швейцария за родината си, ще сънува Константинопол като руски Царьград.

„Константинополь – рано ли, поздно ли, должен быть наш…“[7] Руско-турската война и по-общо кризисното изостряне на Източния въпрос, който навлиза през пролетта на 1876-а в гореща и кървава фаза, довела в крайна сметка до реалнополитическото прекосяване на Дунава от руските войски на 12 април 1877 г., е ключова тема в Дневник на писателя, списанието с един-единствен автор, редактор, издател, собственик и сътрудник в лицето на Достоевски. Политиката на Руската Империя на Балканите е кайросът на Дневник на писателя. „Кулминацията на източната криза съвпада по време с периода на може би най-активната журналистическа дейност на Достоевски.“[8] За първи път концепцията на последния журналистически проект на Достоевски е формулирана в Бесове от любовницата на Ставрогин Лизавета Тушина, която се обръща за редакторска и издателска помощ към консервативно-революционния конвертит Иван Шатов. Лизавета Николаевна си представя един копипейст компендиум на материали от пресата, излезли в рамките на една календарна година, който „би мог[ъл] да обрисува цяла една характеристика на руския живот през цялата година“ (БЫ Х, 103). Нещо като годишен архив на ФБ-Група „Единна Русия“, администрирана от Лизавета Тушина и Иван Шатов. „Това би била, тъй да се каже, картина на духовния, нравствения, вътрешния руски живот през цялата година.“ (БЫ Х, 104) Въобразеният в Бесове – половин век преди едноименното консервативно семейно списание – reader’s digest под редакцията на имагинерния тандем на младежката ляворадикална фасцинираност (Тушина) и консервативно-революционната конверсия (Шатов) неочаквано ще се реализира пет години по-късно в реалния Дневник на писателя. „[В] края на живота си авторът на „Дневника“ отново се обръща към идеите на утопичния социализъм – този път в руския им вариант […] [и]деята на общинния социализъм, своеобразно пречупена, съединена с ʻпочвеничествотоʼ“ (НС 105). Някогашният млад петрашевец и сегашен стар нечаевец е приготвил за малко преди края последната си изненада. От този финален обрат най-изненадани са, разбира се, ортодоксалните консерватори, тези, които (биха искали да) имат Достоевски за необратимо техен човек (и до този момент са го постигали). „Трябва да се помни, че към средата на 70-те години обществената репутация на Достоевски е изглеждала доста еднозначно. Авторът на „Бесове“ […] се е явявал пред лицето на общественото мнение като талантлив белетрист, изменил на идеалите на своята младост и присъединил се към дясното, охраняващо статуквото крило на руското общество.“ (НС 40) Най-лесна е, както обикновено, играта на либералите – към които по-късно успешно ще се присъединят болшевиките – по натякването на измяната. По-съществен е обаче „приятелският огън“ отдясно. „На най-рязка критика „Дневникът“ е подложен от страна на либералната преса. Заедно с това моносписанието на Достоевски не получава никаква реална подкрепа „отдясно“, а понякога дори бива удостоявано с враждебни нападки от тази страна.“ (НС 44) Самият Достоевски открито полемизира в Дневник на писателя с водещите либерални и консервативни издания, „без да закача опонентите ʻотлявоʼ“, конвертитът му с конвертит. „Ляв“ ли е обаче късният Достоевски в публицистичното си осветляване на Източния въпрос и на реалната политика на Руската империя на Балканите? Или ако формулираме въпросът в по-слаба форма: съвпада ли осветлението на събитията в Дневник на писателя с официалната политика на царското правителство?

Преди всичко трябва да се отбележи, че самият Цар Освободител първоначално не е горял от желание да продължи политиката си на Балканите с други средства по Клаузевиц. „Аз се старая с всички сили да уреждам мирното разрешаване на въпроса, а печатът иска да ме скара с Европа; това не може да се допусне.“ (Цит. по НС 119) С публикациите си в Дневник на писателя Достоевски определено спада към онези в „печата“, които със сигурност искат да скарат Александър ІІ с Европа. Травмата на Кримската война обаче, изгубена от баща му, още е свежа. Царят Освободител е подтикван към война с Османската империя както отдясно (славянофилите), така и отляво (руската емиграция). „По този начин, дори убедените противници на властта напълно допускали използването на държавната мощ на царска Русия като външна сила, която обективно способства на делото на националното освобождение.“ (НС 121) Защитавайки Херцен от упрека в славянофилство, който му отправя Бакунин във връзка с позицията му по въпроса за освободителната ролята на Русия, Н. Огарьов сравнява тази роля със силата на гравитацията. „Но ти [т.е. Бакунин, б. м., В. С.] не може да не виждаш, че рано или късно Русия и само Русия (защото няма кой друг) ще се притече на помощ за освобождаване на славяните. Този стремеж е историческо притегляне, което също толкова не може да се избегне, колкото земното притегляне.“ (Цит. по НС, пак там) Спрямо тези вътрешни дебати в лявата емиграция, в които единственият ляв „западник“ се оказва Бакунин[9], марксисткото виждане по въпроса за освобождението на славяните неочаквано се позиционира от страната на левите „славянофили“ Херцен и Огарьов – и съответно от страната на една квазибисмаркова реалнополитическа сила на гравитацията. С думите на Фридрих Енгелс: „[Д]окато те [християнските поданици на Портата, б. м., В. С.] остават под игото на турското владичество, те ще виждат в главата на гръко-православната църква, в повелителя на 60 милиона православни, независимо какво представлява той в други отношения, своя естествен освободител и покровител“ (Цит. по НС, пак там). Макар че сигурно няма да са много щастливи с политически некоректните формулировки на родител № 2 на марксизма, касаещи „османското присъствие“, новите леви едва ли ще имат нещо да възразят на реалнополитическата му логика на гравитацията на „естествения освободител“.

На фона на тези реалнополитически леви славяно-, а и русофили Достовески от Дневник на писателя стои като консервативно-революционен „сънувач“ (А. Илков), някакъв десен вариант на Бакунин. Този десен Бакунин (иска да) вярва в етичността на имперската сила на гравитацията, както левият (иска да) отстоява до горчивия край освобождението, винаги вече несъстояващо се като дело на самите освободени. И в двете визии за освобождението – етично-имперската и автономно-анархистичната – Освобождението на България остава в сферата на художествената литература. Трябва да мислим това място като достойно. Съдбата на конвертита – от Испания през ХV век до Русия през ХІХ-ти – често е била страстно да гради месианистично-провиденциалистки конструкции, които ще го смажат, когато станат държавнополитическа реалност. Трябва да мислим тази страст като достойна. „Утопическото разбиране на историята“ на късния Достоевски – Константинопол трябва да бъде наш – за щастие на консервативно-революционния сънувач не се реализира нито от Руската империя, нито от СССР.

Когато близо година по-късно утопическото разбиране на историята най-сетне добива някакви реални очертания с дългоочакваното прекосяване на Дунава от руските войски, тези очертания са следните: 1) самодържавие и народност: „самият народ се вдигна на война начело с царя“[10]; 2) аналогия с войната срещу Наполеон: „народна война“ (ДПА 96); „Александър І е знаел за тази наша своеобразна сила, когато казал, че ще си пусне брада и ще отиде в горите заедно със своя народ, но няма да положи меч и няма да се покори на волята на Наполеон“ (ДПА 98); 3) православие (Русия) vs. еврейски капитализъм (Европа): „Трепнаха сърцата на нашите изконни врагове и ненавистници […] трепнаха сърцата на много хиляди европейски чифути [жидов] и на милиони чифутстващи [жидовствующих] с тях „християни“ […] ако ние поискаме, то нас няма да ни победят нито чифутите на цяла Европа взети заедно, нито милионите на златото им, нито милионите на армиите им“ (ДПА 97, курсив в оригинала); 4) пацифизмът като буржоазна идеология: „стигат ни вече тия буржоазни нравоучения!“ (ДПА 98); „Борсаджиите например изключително много обичат сега да приказват за хуманност“ (ДПА 101). Теодицеята на войната на Достоевски използва аргументи, познати от Ернст Юнгер, друг ключов консервативен революционер. „Само изкуството поддържа още в обществото висшия живот, буди душите, заспиващи в периоди на дълъг мир.“ (Пак там) Консервативно-революционната утопия от лятото на 1876-а е отстъпила място на фрустриращите реалности на една теория на официалната народност от времената на Николай І, обикновения руски антисемитизъм и една естетизация на войната, лишена от всякаква литературна продуктивност (за разлика например от Ернст-Юнгеровата). Използваната в аргументацията критика на буржоазната идеология взима най-лошото и от двата свята на левия радикализъм и консервативната революция. Доскорошният консервативно-революционен сънувач на Константинопол се пробужда в една политическа реалност, която отчаяно се нуждае от естетическо „спасение“ – и както писателят, така и редакторът (и издател) на Дневник на писателя усеща това. Априлският раздел на книжката от 1877 г., започващ с коментар на току-що избухналата Руско-турска война, включва веднага след него единствения фикционален текст в тази военновременна годишнина на Дневника – „фантастическия разказ“ Сънят на смешния човек.

Героят аз-разказвач на Сънят на смешния човек е кръстоска от Кирилов и Ставрогин – планира да се самоубие като единия и сънува земния рай като другия в своята изповед (в инкриминираната глава У Тихон) – който разказва за себе си като Човека от подземието. Подобно на Кирилов той не спи нощем – но неочаквано заспива и сънува съня на Ставрогин. Той също е „обидил“ малко момиченце (макар и не в сексуалния смисъл на думата), но за разлика от случая Ставрогин тук тъкмо обиденото дете го спасява от самоубийство и му помага да заспи и да сънува своя сън, който го пробужда за нов живот. Макар да не извършва Ставрогинския грях stricto sensu, героят е причинител на грехопадението в сънувания рай. Той е нулевият пациент, носителят на трихинелата от кошмара на Разколников в епилога на Престъпление и наказание. В разказа си за процеса на грехопадение аз-повествователят на Сънят на смешния човек цитира ключова теза от предходния коментар към началото на Руско-турската война, все едно освен разказвач и сънувач е и читател на Дневник на писателя. Двайсетина страници по-рано публицистът е написал: „явно е вярно, че истината се заплаща само с мъченичество“ (срв. ДНА 95, курсив мой, В. С.). Още при първото натъкване на това твърдение в публицистичния текст усещаме някакъв актуалнополитически фалш, автобиографичната му обоснованост влиза в рецептивен дисонанс с аргументативната му употреба в контекста на теодицеята на войната. Екзистенциалният капитал на писателя, първородството на уникалния му опит бива шитнато от идеолога на една война за жълти стотинки, за паница леща. Писателят няма как да не усеща това и няма как да не знае, че читателят, вярващ на големия автобиографичен наратив на страданието[11] – и въз основа на него вярващ на писателя – също ще го усети. Затова писателят ще цитира публициста, пренасяйки екзистенциално-автобиографичната истина от журналистическия контекст на актуалнополитическия коментар към началото на Руско-турската война във фикционалния на „фантастическия разказ“ Сънят на смешния човек. „Те познаха скръбта и обикнаха скръбта, те жадуваха за мъчение и казваха, че Истината се достигала само с мъчение.“[12] Пътят на грехопадението, от който използваната в публицистичния текст екзистенциално-автобиографична истина сега се оказва етап, е постлан с подобни употреби на истината. Приложен към политиката – пък била тя и месианистична – големият автобиографичен наратив на страданието се оказва причинител на грехопадението. Фантастиката на Сънят на смешния човек трябва да спасява истинността на публицистичното слово. Фикцията трябва да спаси истината от човека от подземието на високата идеология.

Сънят на Ставрогин, който пет години по-късно Сънят на смешния човек ще разгърне в „космологичен“ и сотериологичен план, е може би най-мъчителният – по-мъчителен и от блудството с детето и самоубийството му – пасаж на неговата изповед. На път в Германия, той пропуска гарата си и слиза на следващата, за да хване обратния влак. Така попада през ясен пролетен следобед в „мъничко немско градче“ (БЫ ХІ, 21). Той не бърза заникъде, влакът му е чак в 11 през нощта. „Хапнах хубаво и тъй като цяла нощ бях пътувал, заспах чудесно след като се наобядвах някъде към четири следобед.“ Описанието на ужаса е едновременно трезво и идилично. Делово разомагьосващо е мотивиран генезисът на съновидението. „В Дрезден, в галерията, има картина на Клод Лорен, по каталог, мисля, се води „Ацис и Галатея“[13], но аз винаги я наричах „Златния век“, сам не зная защо. Бях я виждал и преди, а сега, преди три дни, минавайки оттам, пак я мярнах. Тъкмо тази картина ми се присъни, но не като картина, а като нещо било наистина.“ Кътче от гръцкия архипелаг, земен рай, деца на слънцето – высокое заблуждение! – под „полегатите лъчи на залезното слънце“. Сънуващият се събужда, облян в сълзи, „за първи път в живота си буквално“ плачещ. И тогава идва дежавюто, свързващо идилията с кошмара, „когато по същия начин се лееха полегатите лъчи на залязващото слънце“ (БЫ ХІ, 22). Меката залезна светлина на идилията е вече видяна веднъж в кошмара.

[1] Достоевский, Ф. М. Идиот [1869]. – В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 8, 1973, с. 25.

[2] Редом с Идиот като единствения роман на Достоевски, написан в чужбина, нека припомним отново и новелата Вечният съпруг (1870), имаща обема на short novel (малко над 100 стр. – обема на Бедни хора и Двойник). Срв. „космическия“ Дон Кихот, реещ се в безтегловност в Соларис (1972) на А. Тарковски. В показанията си пред Секретната следствена комисия през юни 1849 г. Достоевски споменава за един от членовете на кръжеца на Петрашевски, смятан за „истинна, дагеротипно вярна снимка на Дон-Кихот“. – Достоевский, Ф. М. „<Показания Ф. М. Достоевского>“. В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 18, с. 153.

[3] Достоевский, Ф. М. Идиот, с. 452. В тирадата на княз Мишкин, предшестваща счупването на „огромната, прекрасна китайска ваза“ и епилептичния припадък, експлицитно се появява думата почва.

[4] Лев Мишкин носи освен това името на родоначалника Аслан („Лъв“) Челеби-мурза, срв. Волгин, И. Родиться в России. Достоевский: начало начал, с. 48 (бел. 2). При разпитите по време на следствието срещу кръжеца на Петрашевски Достоевски е запитан дали някой си „Аслан“ е посещавал петъчните сбирки, срв. Достоевский, Ф. М. „<Показания Ф. М. Достоевского>“. – В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 18, с. 172. Отговорът му е: „Не знаю господина Аслана.“

[5] Достоевский, Ф. М. Идиот, с. 481.

[6] Пелевин, В. Transhumanism Inc., с. 115. Трийсет години по-рано, в Принцът на Госплан протагонистът проиграва във въображението си имперската траектория на Русия без комунизма: „Запалвайки цигара, той обикновено дълго гледаше многоетажния блок – звездата на шпила му се виждаше леко отстрани и заради ограждащите я венци изглеждаше като двуглав орел; като я гледаше, Саша често си представяше друг вариант на руската история, по-точно друга нейна траектория, завършваща в същата точка – строителството на същия блок, само че с друга емблема на върха“. – Пелевин, В. „Принц Госплана“. В: Пелевин, В. Повести и эссе, с. 115.

[7] Достоевский, Ф. М. „Утопическое понимание истории“, Дневник писателя 1876 [юни]. – В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 23, 1981, с. 48 (многоточие в оригинала). Това е рефрен в Дневник на писателя, срв. броя от март 1877: „Константинополь должен быть наш“ – Достоевский, Ф. М. „Самые подходящие в настоящее время мысли“, Дневник писателя 1877. В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 25, с. 74 (курсив в оригинала). И също: „програмата бе вече дадена: българите (болгаре) и Константинопол“, пак там, с. 72.

[8] Волгин, И. Ничей современник. Четыре круга Достоевского, с. 117. По-нататък цитирам книгата на Волгин в текста със сиглата НС.

[9] „В. И. Ленин, осъждайки реакционните тенденции на романа на Достоевски [т.е. на Бесове, б. м., В. С.], в същото време, по свидетелството на В. Д. Бонч-Бруевич, ʻказвал, че при четенето на този роман не бива да се забравя, че тук са отразени събития, свързани с дейността не само на С. Нечаев, но и на М. Бакунин. Тъкмо по същото време, когато са се писали „Бесове“, К. Маркс и Ф. Енгелс са водели ожесточена борба против Бакунин. Работа на критиците е да изяснят кое в романа се отнася до Нечаев и кое до Бакунинʼ“ (БЫ ХІІ, 256).

[10] Достоевский, Ф. М. Дневник писателя 1877 [април]. – В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 25, 1983, с. 94. Цитирам по-нататък в текста със сиглата ДПА.

[11] Пръв ще концептуализира страданието – във философски, ницшеански avant la lettre регистър – Човекът от подземието: „Та страданието е единствената причина на съзнанието.“ – Достоевский, Ф. М. Записки из подполья, с. 119.

[12] Достоевский, Ф. М. Сон смешного человека [1877]. – В: Достоевский, Ф. М. Полное собрание сочинений в тридцати томах, Т. 25, 1983, с. 116 (курсив мой, В. С.).

[13] Достоевски открива за себе си картината на Лорен при първия си престой в Дрезден през пролетта-началото на лятото на 1867 г., срв. Frank, J. Dostoevsky: The Miraculous Years, 1865-1871, 203 (б. м., В. С.).

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Светла Караянева – Всеки е дошъл отнякъде

Петко Дурмана, Езеро 43, дървета 62

ВСЕКИ е дошъл отнякъде.

Всеки е заварил някого.

И да чуеш: „Добре дошъл!“

И да кажеш: „Добре заварил!“

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Здравка Шейретова – Моята азбука на войната

Росен Тошев, Иди на…

Абсурд – бомби, разкъсват невинни, деца

Битка – загуба, в която не се печели

Война – изкривени от ужас лица

Грохот – светове срутени, домове изгорели

Днес – времето в бъдеще няма

Ева – сама е, без дом и Адам

Живот – безнадеждност и рани

Закон – погазен без срам

Ирод – зловещ убиец без свян

Йов – изпитание от нашия Бог

Каин – братоубиец по план

Любов – мъртва без диалог

Мир – свят в сговор, хармония

Нощ – безсъние между вечер и сутрин

Очи – широко нагоре отворени

Плач – вопъл срещу Русия и Путин

Рак – метастази роят се дълбоко

Свобода – изначална, горда и жива

Тъга – израства все по нависоко

Украйна – брани се без алтернатива

Федерация – фалш и фиаско

Хеттрик – това заслужават, това ще получат

Шут – от световната сцена и място

Щурм – ще се върне като в поличба

Юмрук – пръстите свити в единство

Ядро – украинци пазят сърцето си материнско

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Стефан Кисьов – Аз разбирам болките

Росен Тошев, Иди на…

Аз разбирам болките на българските путинисти, и искам да ги уверя, че част от мен, една наистина не особено голяма част, им съчувства. Защото знам колко е тежко да виждаш, как обектът на твоето обожание, бившият, обвит с романтика, чар, мистика офицер от КГБ, превърнал се в президент четвърти /или пети?/ мандат, сега е наричан военнопрестъпник, убиец, хейло, путлер и т.н. Тежко е, наистина, мъчително. Та той, според тия български путинисти, е една възвишена, отдадена на великата славянска, православна идея душа. Един полу-бог, светец, ангел на доброто и лошо, който като един свети Георги биещ се срещу змея, се бори с атомните заплахи, спасява майка-русия и т.н. А целият, лош, глупав, джендърски, наркомански, капиталистически свят сега е срещу него, нашия Володя! Мъка, мъка, путинофилска! Няма ли край тоя кошмар?

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Дора Радева – Война

Петко Дурмана, Езеро 43, дървета 62

Война

И тази пролет ще цъфнат

момините сълзи и лалетата

и ирисите после

в двора на моята малка

горска къщичка с чувство за хумор.

Кой?

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

Златомир Златанов – Означаващи и снаряди

Петко Дурмана, „Двоен портрет #3 – Цар Бомба” (Путин и бомбата)

Към войната са отнесени всякакви аргументирани глупости, които не издържат. Колапсът на един аргумент е функция на неговото разгръщане.

И всякакви дежа-вю дефилират в зрителното поле, но ние вече знаем от Лакан – Погледът е завеса като идол на отсъствие. Секретът на триумфиращата визия е в организацията на неочевидното.

И всякакви морализаторства, но ние вече знаем – етиката на Реалното е извън символни координати.

Господарското означаващо е несъзнавано и неуправляемо в траекторията от невъзможност към импотентност – и какво друго трасира, освен мрачното увлечение по смъртта, която прави от всички нас фикции и само като фикции се справяме с него..

Разделителните линии, те не са геополитическа маркировка, а бразди в Реалното, cut in the Real, съживявани отново и отново под натиска на повторението – и какво друго протича през тях, ако не влечението към смъртта…

Cut in the Real – отнася се до изначалното примордиално означавашо на Лакан – как да се преведе – разрез в Реалното, къртене в Реалното? Нещо като ангели с огнени мечове – изглежда абстрактен генезис, но с какво е по-различен от структурните перверзии на реалните политики и военни стратегии?

Именно Реалното на войната – не само че е непреводимо, но и невъзможно за символизация, да кажем че е пречката за формализация, импас, твърдото ядро във всеки опит за символизиране, кост в гърлото, дедлок, препречен достъп до истината.

Половинчати истини на половинчати светове, бленуващи пълна победа…

Тогава как една империя на истината ще смени империята на лъжата, каквито са геополитическите фантазии на такива като Дугин?

Истината винаги е под формата на фикция, на семблант, привидност, не защото е фалш, а защото истинският свят винаги е липсващ.

Имаме достъп единствено до семблатизация на света, до непризнаване и елиминиране на неочевидното – това са реалните глупости, нали, да присвояваш в дискурс Реалното на войната, да наречеш бомбените завеси „идол на отсъствие” сигурно звучи цинично, но не вършат ли точно това предположително знаещите, пълководците и анализаторите, шринк докторите, коментаторите…

Спомням си как Путин произнасяше Россия със съскащите съгласни. Именно, това е имперското означаващо, което прорязва Реалното (the cut in the Real), за да артикулира свят, но всъщност да причини дори не липса на свят, а самата безсветовост (Weltlosigkeit). Означаващите подредени в структурната перверзия на бомбени завеси от снаряди

Имперското примордиално означаващо винаги под опасност, която самото то е инвестирало в свят несвят. И съответстващите тъпи разсъждения – за какво ще е този свят, ако я няма Россия?

Господарското означаващо на една травма, конвергираща с некро-отпадъци, които й дават живот, съживяват я под натиска на повторението в откровено влечение към смъртта.

Означаващото, конвергиращо с летални отпадъци, за да артикулира обект-причината на имперско желание. Смъртта е моят герой заради една вечна империя като форма на вечно измиране.

Нищо не може да се каже за нещата извън репрезентация.

И тук аз не психоанализирам. Припомням трите постулата на Фройд –

Управлението е невъзможно

Преподаването е невъзможно

Психоанализирането е невъзможно

И ако това изглежда абстрактно, тогава какво да кажем за геополитическите фантазии на един диктатор?

И ако никой не е убедителен, защо да не прибегнем до вицове – в един руски затвор трима се питат за какво са осъдени. Първият казва, аз бях против Попов и получих десет години. Вторият казва, аз бях за Попов и получих десет години. Третият казва, аз съм Попов и съм осъден до живот.

Именно Попов е Реалното на политическото, симптоматичният възел.

И той не може да бъде разплетен, а само съсечен, за да бъде произведен отново, запълващ пролуките на Реалното както вегетацията покрива раните на войната.

Означаващото кърти в Реалното и произвежда реалност, жалки производни субститути – кога Россия е станала Россия и защо Америка отказва да се нарича империя – ето как от нищото на неочевидното Реално се откъртват жалки империи на суверенното нищо, годни да унищожават в самоунищожение, повтаряйки хегелианската схема – от нищото през нищото към нищото.

Именно, травмата на къртещи означаващи и принудата на повторението, съживяващо травмата като заспал вулкан, за да прехвърчат отново и отново къртещи означаващи и реални бомби и снаряди, префигуриращи нещо като свят, светове на не-всичко, за да бъдат засимптомени в семблант светове – до следващия разрив и къртене –пришиваме метафорични имена – предвоенен период, следвоенен, докато войната пронизва от всички страни слабо закрепени и компрометирани светове.

Россия, Дойчланд юбер алес, Америка фърст – не, благодаря

Всяка глобализация е предвождана от милитаризация. Само агресията на влеченията, на влечението към смъртта отключва реалност, за да я дереализира.

Симптомът идва от бъдещето. Сега ние чакаме нещо да затапи плачевната ситуация на война като съживяване на изначална травма под натиска на повторението. Чакаме по-различен симптом, напразно.

Войната не може да се психоанализира, само последиците.

Самото психоанализиране е невъзможно.

Това е етиката на Реалното, която всички не знаем, че знаем.

Ако за Хегел Бог е selbstbewust, за Лакан Бог е несъзнаван.

Аналитикът е в позиция на „обект а”, боклук.

Но човешките животни които се вмъкват в господарското означаващо или в позицията на аналитика, си въобразяват, че могат да управляват и те управляват импотентността на господарското означаващо, конвергиращо с обект-причината на желанието, тоест с боклукчивото, като постоянно сменят позициите си – днес управляващ, утре си боклук.

Забравихме ли наставленията на свети Павел за встъпващите без разлика в Царството Божие, за възлюбените в Христа – нито грък, нито евреин, нито обрязан или не – без разлика.

Човешките животни оковани в разделителни линии под диктата на Едното – те историзират влечението към смъртта, истеризират го, не е ли това гледката, семблатизацията на истината, милитаризацията…

Войните за суверенното нищо, за призрака на една Елена, войни заради една сянка – това ли е неочевидното и кой триумфира в него?

Войните като мрачната същност на безсъщностни светове.

Златомир Златанов

15.03. 2022

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X

RapisGames – Завиждам на мама

Петко Дурмана, Дете 39/31

Завиждам на мама, тя гледа 1 и 2 канал, където всичко е наред, само трябва малко да се потърпи, и тя искрено вярва в това, и е готова да търпи, заради прекрасното бъдеще. Гледам я и ми се плаче… Това е същото като да кажеш на дете, че Дядо Мраз не съществува…

Превод от руски Владимир Сабоурин

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 34 (извънреден), април, 2022, ISSN 2603-543X