1965

29 октомври. „Със „Соларис“ ще се заеме лично Тарковски.“ (Писмо на Аркадий до Борис Стругацки)

1969

Октомври. Т. се среща със Станислав Лем, който се държи високомерно и грубо. „Той засне не „Соларис“, а „Престъпление и наказание“ (С. Лем).

1972

Началото на годината. Т. завършва монтажа на Соларис, който „ще се окаже най-успешната му творба в зрителско и финансово отношение“ (Евгений Цимбал).

23 февруари. „Трябва да се екранизира несъстояла се литература, в която обаче има зърно, което може да се развие във филм, и който, на свой ред, може да стане изключителен, ако приложиш към него способностите си.“ (Андрей Тарковски)

6 юни. Първа (случайна) среща и запознаване на Тарковски и Аркадий Стругацки в ресторанта на Дома на литераторите. Т. обещава да покани Аркадий на прожекция на Соларис в „Мосфилм“.

Краят на лятото. Пикник край пътя излиза в четири поредни броя на ленинградското сп. Аврора „почти необезобразен“ (Борис Стругацки).

1973

26 януари. „Току-що прочетох научно-фантастичната повест на Стругацки „Пикник край пътя“. И от това [също] може да се направи бърз сценарий за някого.“ (А. Тарковски) Първата идея е за писането на сценарий, който да бъде предложен на друг режисьор. По това време от сценарии се печели по-добре, отколкото от режисура.

1974

Есента. Списък на филмите, които Т. иска да направи: Идиот (по Достоевски), Смъртта на Иван Илич (по Толстой), биопик за Достоевски – и, „може би“, Пикник край пътя. Планира преди Идиот да заснеме набързо някакъв филм за пари, избира да екранизира Пикник край пътя.

1975

4 януари. „А какво би станало, ако вместо младеж в „Пикника“ се сложи жена [като сталкер, б. м., ВС]?“ (А. Тарковски)

6 януари. „По нещо желанието ми да правя „Пикник“ прилича на състоянието ми преди „Соларис“. Сега вече мога да разбера причината. Това чувство е свързано с възможността легално да се докосна до трансцендентното.“ (А. Тарковски)

27 март. Тарковски на гости у Аркадий Стругацки, за първи път признава, че той иска да е режисьор (а не сценарист) на филма по Пикник край пътя. Аркадий е много щастлив, че Тарковски ще е режисьорът.

24 октомври. „Заявка“ на братя Стругацки пред „Мосфилм“ за изготвянето на сценарий на „пълнометражен цветен художествен филм с условното заглавие Машината на желанията“.

19 декември. „Тарковски. Човек = животно + разум. Има още нещо: душа, дух (морал, нравственост). Истински великото м.[оже да] б.[ъде] безсмислено и нелепо – Христос.“ (Борис Стругацки)

1976

Краят на януари. Първият вариант на сценария (Машината на желанията) е готов. Т. прочита сценария – и започва процесът на безкрайното редактиране.

11 февруари. „Пишем за Тарковски, а той е гений и, следователно, не може да му се угоди.“ (Б. Стругацки)

Краят на март. Готов е вторият вариант на Машината на желанията. „В сценария […] няма никакви такива храсти [неопалимата къпина от Огледалото, б. м., ВС]: нормална съветска (добра) фантастика – с ясен сюжет, с герой, голямо количество необикновени събития, с нравствен извод.“ (Леонид Нехорошев, гл. редактор на киностудия „Мосфилм“)

9 април. „Хрумна ми, между другото, нелоша, според мен, идея за сценария. Трябва да направим Алън [едно от първоначалните имена на Сталкера в сценария, б. м., ВС] сакат или урод (еднорък, или гърбав, или с ужасяващ белег, или с перде на окото, или едноок)“ (Б. Стругацки). Т. харесва идеята – както при Бунюел. „В окончателния вариант на филма Сталкерът е „убог“ преди всичко в психологически смисъл. Той се превръща в нещо средно между блажен, юродив и раннохристиянски пророк, наистина болен, кашлящ, дишащ шумно и накъсано.“ (Е. Цимбал)

Първата половина на април. Заглавието на сценария е променено от Машината на желанията на Сталкер, „гангстерският филм се превръща във философска притча“ (Е. Цимбал).

30 април. Т. получава разрешение от „Мосфилм“ да започне избирането на места за снимки в натура. Изходната визия на Т. е пустиня или полупустиня, където от двайсетина години стои изкорубена военна техника, иска да огледа места в Средна Азия, където никога не е бил. Предлага да започнат търсенето от Туркмения. Барханите (дюните) от туркменската пустиня по-късно ще се появят в павилиона на „Мосфилм“. В Ташкент (Узбекистан) Т. среща Александър Кайдановски – бъдещият изпълнител на ролята на Сталкера – и го моли да изпрати свои фотопроби за кастинга. В този период контактите със Стругацки се прекратяват, възприема ги като „маврите, които са си свършили работата“.

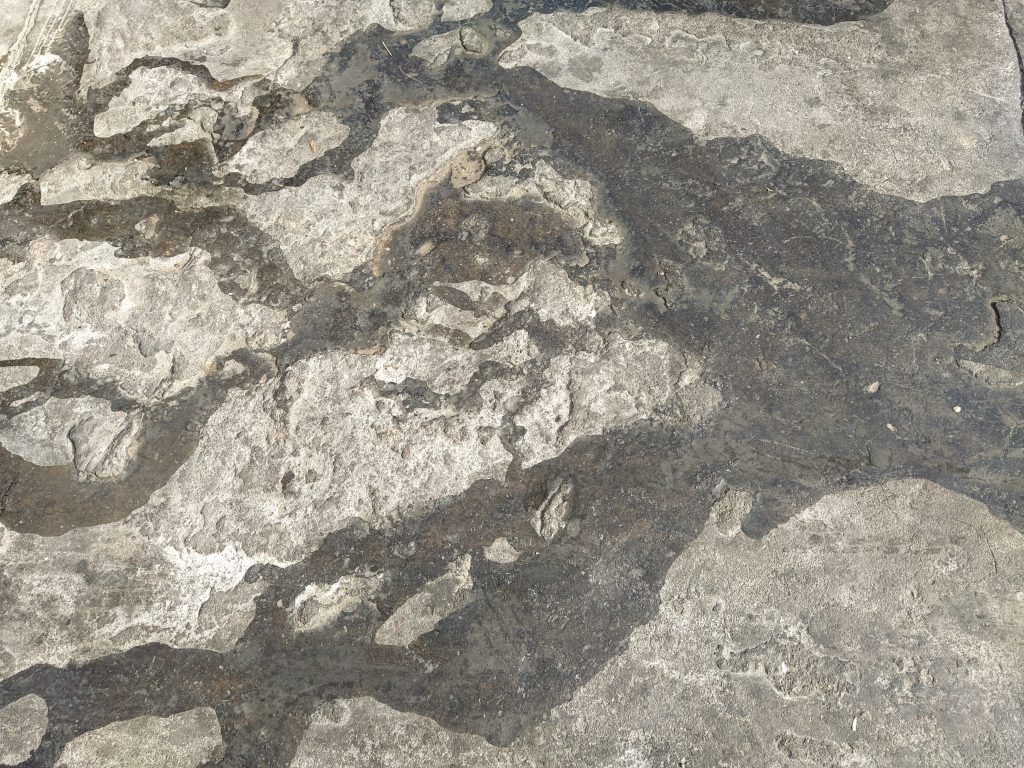

Началото на юли. Най-накрая Т. харесва място за екстериорни снимки в Исфара (Таджикистан). „Пристигнахме на много необичайно място, наречено Исфара, където се срещаха пустиня, гора, тръстикови блата и фантастически, неправдоподобни планини, приличащи на гигантски окаменели човешки мозъци. Някакъв лунен пейзаж. […] Освен това там имаше старинни китайски каменовъглени шахти, изоставени преди повече от сто години […] беше останала полуразрушена железопътна линия, наклонили се стълбове, преобърнати вагонетки.“ (Александър Боим, художник на продукцията) Непосредствено преди Т. мястото е оглеждано за снимки в натура от Микеланджело Антониони.

20 септември. Продуцентът на филма Вили Гелер пише до зам. ген. директора на „Мосфилм“ с молба за разрешаване на предварителни разходи, сред които е закупуването на Ленд Ровъра – „7 хиляди рубли“. Разрешението за закупуването на Ленд Ровъра е получено на 29 декември. Подготовката за експедицията в Таджикистан е към своя край.

1977

31 януари. Земетресение край Исфара с магнитуд 6,1. Многобройни жертви и разрушения. На снимачната група е отказано настаняване в града.

15 февруари. Започват снимачните работи в павилион, „Жилището на Сталкера“. „Аркадий Стругацки, който страстно мечтаел да попадне на снимачната площадка на Тарковски, е разочарован, че не е поканен за началото на снимките. Първо, той много иска да види как снима един гений, второ, той толкова дълго е чакал този момент, че би отпразнувал, разбира се, това събитие. От страна на режисьора обаче вниманието към сценаристите в тези дни е минимално.“ (Е. Цимбал) В този период Т. гледа Виридиана и (за първи път) Симон Пустинника, както и Бергман (Седмият печат, Мълчание, Персона, Срам, Шепот и викове и др.). Стругацки не са поканени на прожекциите. След заснемането на „Жилището на Сталкера“ спешно започва търсенето на нова натура.

Началото на март. Намиране на натура в металургически комбинат в Запорожие. „Димящи грамади от вкаменена шлака с металически потичания, преливащи във всички цветове на дъгата.“ (Георгий Рерберг, оператор) Отказ от този подходящ екстериор поради здравословни съображения – Запорожие е „едва ли не на първо място в СССР по заболявания от рак на белите дробове“ (в Естония обаче нещо подобно няма да се окаже пречка). Търсене на снимачна натура в Подмосковието. „Черно, отровено, зловонно езеро с чудовищна екология край охладителните кули на един от московските ТЕЦ-ове“ (А. Боим). Този екстериор ще бъде използван за заснемането на сцената с носенето на Маймунката на конче.

Втората половина на март. „Него [Т., б. м., ВС] подсъзнателно го влечеше към средноруската полоса. Натурата и литературата са свързани в киното в колосална степен.“ (Г. Рерберг) „Андрей Арсеневич започна вероятно да търси това, което преди това намери за себе си при работата върху „Соларис“ и окончателно обикна при „Огледалото“: тишината, съсредоточеността и магията на средноруската природа.“ (Е. Цимбал)[1]

Първата половина на април. Откриване на изоставена хидроелектроцентрала на р. Ягала на трийсетина километра от Талин. „И ето тук сценарият започна да се пропуква доста сериозно. Във връзка с абсолютно другия, различен от предписания в сценария, характер на избраната от нас натура.“ (Г. Рерберг)

„Тази електростанция била построена в независима Естония в края на 20-те години и прекрасно работила до 1941-а. При отстъплението на Червената Армия била изведена от строя от нашите войски, след войната се опитали да я възстановят […], но после размислили и зарязали всичко както си е. Оттогава това място малко се е променило за трийсет години, само силно е обрасло с храсти и дървета. […] Беше идеално за снимки поради това, че се намираше в граничната зона, където не пускаха никого без специално разрешение […]. Във въздуха смъдящо смърдеше на алкалии от течащата наблизо река с йодисто-оранжев цвят, в която се изливаха отпадъците на целулозно-хартиен комбинат […] беше приятно да се работи, да не беше само зловонието, идещо от реката. После му свикнахме и престанахме да го забелязваме.“ (Е. Цимбал)

12 май. Финализирането на снимките е планирано за 31 август. „За Андрей Арсениевич „Зоната“ беше главното, другите обекти, смяташе той, могат да се заснемат по-късно, в краен случай дори не в Талин. Пребиваването в „Зоната“ той искаше да снима строго последователно, започвайки от захождането на героите към електростанцията. […] Филмът трябваше да се развива в режим на реално време“ (Е. Цимбал). „Той се стремеше да прави строго, класическо кино на трите единства: единство на мястото, времето и действието. По-голямата част от историята, последователно разказана в „Сталкер“, протича в течение на едно денонощие на едно и също място без големи пропуски във времето и действието.“ (Арво Ихо, естонски студент от майсторския клас на Т.)

Началото на юни. Пристига съобщение от Москва, че проявеният материал е брак. За една седмица се преснима отново всичко, оказало се брак при проявяването. „Мосфилм“ е упълномощен да заяви, че „проблемът е не само в развалената машина за проявяване, но и в ремонта по трасето на парното, поради което поне още три седмици в киностудията няма да има топла вода“. По същото време Евгений Цимбал намира случайно втората изоставена хидроелектростанция, където ще бъде сниман пасажът със „сухия тунел“.

Втората половина на юни. Заснет е целият път до първата електроцентрала и снимачната група влиза вътре в нея.

Краят на юни. Машината за проявяване е поправена и целият заснет дотук материал (40% от целия филм) е проявен. Резултатът е същият: отново брак.

7 юли. Снимките започват за трети път. Отново всичко трябва да започне отначало. Тенденцията към минимализъм на Т. се засилва.

Втората половина на юли. Т. решава да пренесе някои от най-важните епизоди на бента на втората електростанция. Търси се виновен за „безкрайния брак“.

21 юли. Т. намира виновния – оператора Георгий Рерберг.

Краят на юли. Т. узрява за идеята (дадена му от Рерберг), че проблемът се корени в крайна сметка в сценария. Без да признава правотата на Рерберг, Т. привиква на снимачната площадка Аркадий Стругацки. „В нашата страна има само един научен фантаст – това е Карл Маркс. А останалите фантасти съвсем не са научни. Включая нас с брат ми.“ (А. Стругацки) „Андрей, струва ми се, че двама гения на една снимачна площадка идват множко.“ (Г. Рерберг) За женския от двата прегърнати скелета Т. иска перука от естествена коса – рижа (като на съпругата му Лариса Т.). Пред прегърнатите трупове е поставена бутилка от шери „Амонтилядо“.

„В действителност Стругацки е нужен на Тарковски, за да подкрепи по-нататъшните му действия. Режисьорът е решил да се избави от Боим и Рерберг, станали свидетели на неподготвеността му за снимачната работа. На тях можеше да се припише вината за всички неприятности, натрупали се за два месеца и половина снимки.“ (Е. Цимбал) „Един от тях [от братя Стругацки – Аркадий, б. м., ВС] дойде при мен и ми каза, да не се вра в драматургията. Аз отговорих, че не мога да не се вра в подобна драматургия, защото текстът трябва да намери въплъщението си в изображението. Затова тук трябва нещо да се променя.“ (Г. Рерберг) Т. насъсква А. Стругацки и Рерберг един срещу друг, за да реши на техен гръб собствения си проблем със сценария.

„Тарковски изведнъж промени отношението си към сценария, по който беше снимал до този момент. Той започва да смята, че една от главните причини за неудачите е характерът на главния герой и той трябва да бъде променен. Вече са похарчени обаче по-голямата част от парите и от лентата, отпуснати за филма.“ (Е. Цимбал)

Началото на август. Трети брак на лентата. „Тарковски реши да се възползва от това печално обстоятелство, за да започне всичко отначало.“ (Б. Стругацки) За да си осигури чист старт, Т. прехвърля отговорността за брака върху Рерберг. (Реалният проблем е чисто технически – в качеството на лентата и процеса на проявяването й в „Мосфилм“.) Тази маневра позволява на Т. да издейства допълнително финансиране за филма чрез превръщането му в двусериен.

ПТП с камервагена. Смъртта на пъстървите. „За един то кадрите, сниман на този ден, Тарковски пожела да плуват живи риби във водата на електростанцията. На снимачната площадка докараха […] към десет килограма жива пъстърва. […] Не успяха да снимат рибите до края на смяната и я пуснаха в специално направена кошарка с течаща вода, за да се завърши епизодът на следващия ден. Но водата там беше такава, че тези бедни пъстърви изплуваха много бързо с корема нагоре. След плаването в такава водичка те придобиха химически дъх и никой не се реши да ги яде. Аз трябваше да ги закопавам в гората“ (Е. Цимбал).

11 август. Спешно създадена комисия към „Мосфилм“ вменява на Рерберг, че не е провел задълбочени проби на лентата преди началото на снимките на Сталкер. „В Талин снимачната група, намираща се там четвърти месец и неразбираща какво се случва, кога ще приключат снимките и ще може да се върнат у дома, започна да затъва в запой. Пиеха почти всички – от шофьорите и осветителите до механиците и администраторите. В киното пиянството се считаше изобщо за достойно за мъже занимание, можещо да снеме нервното и физическо напрежение. На отбягващите почерпките гледаха като на бели врани.“ (Е. Цимбал)

26 август. Т. признава в дневника си, че цялата снимачна работа дотук е била безсмислена, снемайки от себе си всяка вина. „(Сега Аркадий и Борис се опитват да пренапишат всичко отначало заради новия Сталкер, който трябва да бъде не разновидност на търговец на наркотици или бракониер, а роб, вярващ, езичник на Зоната). Сега всичко наново. Ще стигнат ли силите?“ Т. иска нова лента и отказва да снима до разрешаването на въпроса. Междувременно трябва да се снима колкото се може по-скоро – „екстериорът си отива“ с наближаването на есента.

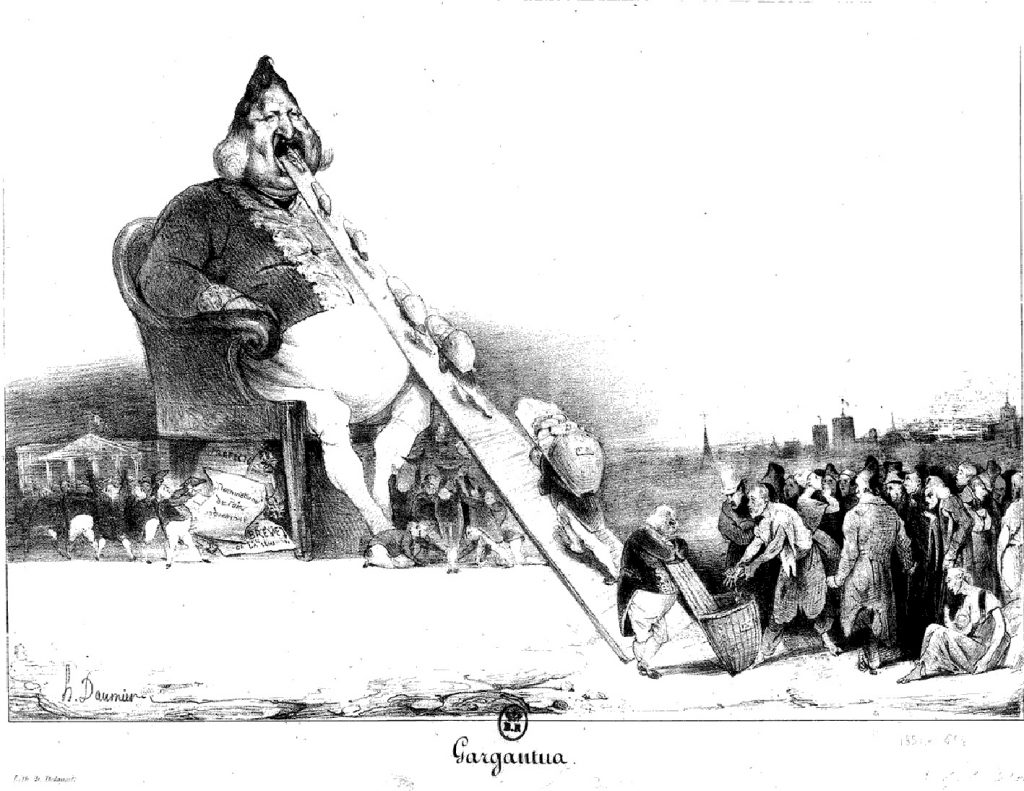

Една от хипотезите около загадката с брака на лентата: изпратеният от ФРГ „Кодак“, на който трябвало да се снима Сталкер, бил даден на първия секретар на Съюза на кинематографистите на СССР Лев Кулиджанов за заснемане на идеологическа държавна поръчка – Карл Маркс. Младите години (Karl Marx. Die jungen Jahre), копродукция СССР-ГДР; а за Сталкер дават залежала на склада лента. Друга хипотеза: лентата за Сталкер била използвана за снимането на партийни конгреси и пленуми (трета версия: за заснемането на Олимпиадата в Москва през 1980).

Началото на септември. Всеки следващ ден в Естония превръща летният екстериор в есенен. „Мосфилм“ и Госкино на СССР най-сетне формулират официалната си позиция по брака на лентата и назначават за виновни Рерберг и началника на ОТК (Отдел за технически контрол) на „Мосфилм“, те получават „мъмрене“. На Т. му се разминава със символично наказание – „забележка“.

Новият юродив Сталкер стимулира Т., който възнамерява да преснеме през останалите на разположение есенни дни всички екстериорни епизоди, чието действие се развива в Зоната. Той се надява да успее да преснеме маршрута на героите до „Стаята, където се изпълняват желанията“ преди настъпването на първите студове.

16 септември. Започват снимките на Сталкер-2. Т. не променя маршрута, но главният герой става диаметрално друг. „По-рано той бе жесток и брутален, командваше и тормозеше спътниците си. Сега става неуверен, понякога просто жалък. Това вече беше юродив, но напълно стерилен, без присъщата на този типаж енергичност и непристойност (като например Ролан Биков в „Андрей Рубльов“ [в ролята на шута, б. м., ВС]). […] Болен, физически слаб, обиден от живота, но последователен в служенето си на Зоната.“ (Е. Цимбал) След налагането на фигурата на новия Сталкер Аркадий Стругацки окончателно напуска снимачната площадка.

20 септември. В Петрозаводск (Карелия) и околностите между 4 и 4:20 сутринта в небето е наблюдавано НЛО, за което съобщават дори централните вестници (включая „Правда“).

21 септември. Заседание на Бюрото на художествения съвет на киностудията. „Не мога да посветя живота си на филм, който за мен е преходен.“ (А. Тарковски) Т. се връща в Талин и продължава преснемането. Необходимият зелен екстериор катастрофално и бързо си „отива“. „А когато застудя и заваляха продължителните есенни дъждове, започна пълна лудост. Късахме изпъкващите сред окапалите листа червени гроздове на шипките. После късахме изобщо всички листа по клоните. Заменяхме ги с докараните от студията пластмасови зелени листа. Снимахме псевдолятна натура. […] Всеки ден увеличаваше мярата на абсурда и безсмислието на случващото се, потъвахме във водовъртежа на безумието. По снимачната площадка тичаха хора с носилки, полагаха чимове на нужните места и през глава препускаха за нова порция чимове зелена трева. Приличахме на луди. По лицата ни се четеше безизходица и отчаяние – и едновременно с това ревностна вяра, че този труд е важен и необходим. Процесът на пресаждането на чимовете почна да отнема по няколко часа. Светлата част на деня намаляваше. Тарковски обаче настояваше да продължаваме снимките, макар да беше ясно, че няма да успеем да преснемем лятната натура.“ (Е. Цимбал)

28 септември. Т. праща телеграма до Госкино: „настоявам на продължаването на снимането по двусерийния вариант на катастрофически отиващата си натура до заповед на Госкино за закриване на филма тчк [точка] Тарковски“.

Началото на ноември. Напускане на Талин.

Началото на декември. „На Александър Кайдановски през нощта му свършват кибритените клечки и той решава да припали от бързовара, без да знае, че при нагряване до висока температура, без да е потопен във вода, уредът се взривява. В лицето и окото на Саша се впиват десетки нажежени металически парченца. Възниква реална заплаха от загуба на зрението.“ (Е. Цимбал)

„Андрей се затваря през зимата, преписва все пак кардинално сценария и през пролетта започва отново снимките. И преснема всичко отново. Това, разбира се, беше възможно само в Съветския Съюз и това можеше да направи само човек като Андрей. За трети път да заснеме все същото, което беше заснето вече два пъти.“ (Г. Рерберг)

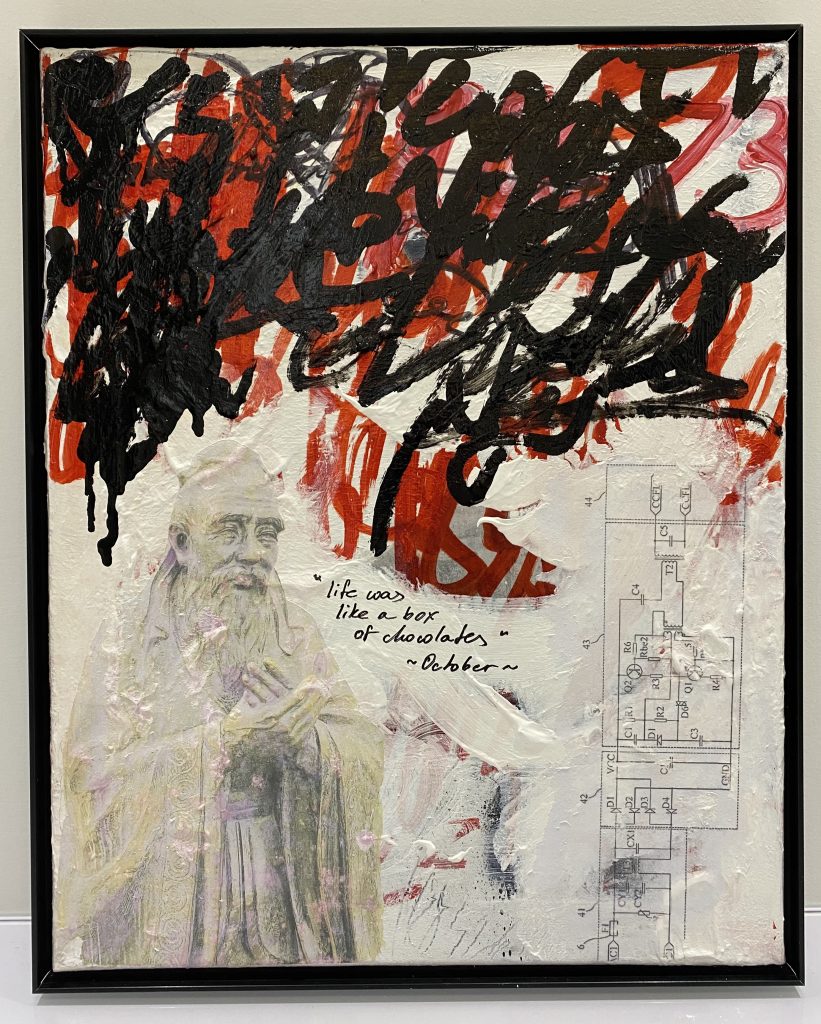

28 декември. „Слабостта е голяма, силата – нищожна. Когато се роди, човек е слаб и гъвкав. Когато умира, той е силен и корав. Когато дървото е още фиданка, то е гъвкаво и нежно. И когато стане сухо и твърдо, то умира. Коравостта и силата са спътници на смъртта. Гъвкавостта и слабостта са израз на свежестта на битието. Защото това, което е затвърдяло, то не ще победи.“ (А. Тарковски цитира Лао Дзъ в дневника си) Цитатът от Лао Дзъ ще влезе в окончателния вариант на филма.

1978

10 февруари. Сталкер е включен в тематичния и производствен план на „Мосфилм“ за 1979 година.

1 март. Излиза заповедта на генералния директор на „Мосфилм“ за възобновяването на продукцията на Сталкер. „Госкино му отпуска допълнително 500,000 рубли и лента „Кодак“, които другите режисьори получават едва ли не по сантиметри.“ (Борис Павльонок, зам.-председател на Държавния комитет на СССР по кинематография.) „Нещо подобно се е случвало единствено при продукцията на съветските суперколоси „Война и мир“ на Бондарчук, „Освобождение“ и „Войникът на свободата“ на Юрий Озеров, където за първи път в съветското кино на екрана се появява Брежнев, чиято роля е изиграна от Евгений Матвеев.“ (Е. Цимбал) Започват снимките на Сталкер-3.

След скандалите и уволненията от миналата година никой от художниците не иска да работи с Т., „Мосфилм“ го назначава за и. д. художник на продукцията. „Тарковски използва художествените и стилови решения, измислени заедно с него от тези, с които той се разделя: Боим, Рерберг, Абдусаламов, Калашников, Воронков. Впоследствие никой от тях не е упоменат в надписите на филма.“ (Е. Цимбал)

4 април. Т. претърпява инфаркт на 46-ия си рожден ден. Получава телеграма с пожелания за скорошно оздравяване от Серджо Леоне.

12 май. Утвърден е окончателният бюджет на продукцията, възлизащ на 915,687 рубли. „Тази сума двойно превишава бюджета на една средна мосфилмовска продукция.“ (Е. Цимбал)

Началото на юни. Завръщане в Талин. Целулозно-хартиеният завод вече е монтирал очистителни съоръжения, в реката няма пяна и смъдящият смрад значително е намалял.

2 юли. Начало на екстериорните снимки. Както и миналата година, заснемането започва с маршрута на героите до първата електростанция. „Този план е снет от интериора на зданието на електроцентралата, сякаш през очите на неведомия разум или същество, намиращо се вътре в нея. Във филма този похват се повтаря няколко пъти, както и насрещните погледи на героите. Протича своеобразен мълчалив диалог между хората, които искат да разберат що е Зоната, и онова невидимо, което ги гледа оттам с безстрастен, отстранен поглед.“ (Е. Цимбал) След инфаркта Т. спира да пие.

„Ние бяхме убедени, че трябва да дадем всичко от себе си за филма, дори ако това изискваше неразумна смелост и пренебрежение към техниката за безопасност. Ние всички бяхме психопати и фанатици, макар и в различна степен.“ (Е. Цимбал)

Веднага след като отпада нуждата от по-нататъшно пренаписване на сценария, Т. прекратява общуването със Стругацки.

Краят на октомври. Връщане в Москва. Снимане на епизода „Излизане от бара“, който е заснет на място, разположено на няколко километра от Кремъл, точно до психиатрична болница, където затварят дисиденти (един от „пациентите“ на заведението е Йосиф Бродски). Декорациите са на не повече от метър от оградата на психиатрията.

Т. изисква Наташа Абрамова, изпълнителката на ролята на Маймунката, да бъде подстригана нула номер, после размисля и нарежда да й сложат кърпа на главата.

Началото на ноември. Започват снимките в павилион. Главната декорация – Стаята на желанията – е изградена, въпреки съпротивата на киностудията, в най-големия павилион на „Мосфилм“. Т. настоява за изработването на дюните да се използва перлит. „С одържимостта и упорството си той вероятно съкращава своя живот и живота на Анатолий Солоницин. И двамата умират от рак на белите дробове.“ (Е. Цимбал)

В декорацията на „Стаята на изпълнението на желанията“ с педантична детайлност се възпроизвежда интериорът на първата електроцентрала в Естония (включително и предсталинистката осмоъгълна теракота).

„Камерата гледа нашите персонажи от вътрешността на стаята на изпълнението на желанията като публиката от зрителската зала. Сякаш „Зоната“ се вглежда в представлението, което разиграват пред нея героите на филма, преценявайки дали си струва или не да изпълнява желанията им.“ (Е. Цимбал)

При заснемането на сцената с епилептичния припадък на Жената на Сталкера Т. така „напомпва“ Алиса Фрейндлих, че при последния дубъл (трети или четвърти поред) с нея се случва реален припадък. „Актрисата започна да се гърчи и мята в реални конвулсии, те ставаха все по-силни, продължаваха вече минута-две, но Андрей Арсениевич не спираше снимането. Княжински [новият оператор, б. м., ВС] на два пъти се откъсваше от камерата и въпросително поглеждаше Тарковски, но той омагьосано гледаше мятащата се в гърчове актриса и шепнешком нареждаше на оператора: „Не изключвай, не изключвай камерата!“ Андрей Арсениевич с жадно любопитство чакаше какво ще се случи по-нататък.“ (Е. Цимбал)

11 декември. Епизодът със „заклинанието на чашите“ липсва в сценария. Снет е без репетиции. Във въздуха летят тополови пухчета, с които реквизиторите са се запасили още миналото лято в Естония. „Не се бяхме разбрали, че една от чашите ще падне от масата, тази идея дойде на Андрей Арсениевич по време на снимането. Той ми даде знак с палеца надолу и аз осъществих поредната режисьорска импровизация. […] Това беше последният снимачен ден, последният епизод и последният кадър на филма.“ (Е. Цимбал)

1979

28 януари. „А ако се развие „Сталкер“ в следващ филм – със същите актьори? Сталкерът започва насила да влачи хора в Стаята и се превръща в „жрец“ и фашист. „За ушите – към щастието“. Вл[адимир] Ул[янов]? Шарик? [от Кучешко сърце на М. Булгаков, б. м., ВС]“ (А. Тарковски).

Първата половина на февруари. Започват да се разпространяват слухове за жесток, стигнал до бой конфликт между братя Стругацки и Тарковски.

[1] Работейки успоредно над безкрайните редакции на сценария на Сталкер и романа Бръмбар в мравуняка, Стругацки сякаш си позволяват леко да изпуснат парата на фрустрацията от постоянно променящите се и често неясни желания и претенции на Т. по сценария с пародийното представяне на търсената от режисьора мистика на средноруската природа: „в курортологията за кратко взе превес идеята, че уж само средната полоса е в състояние да направи летовника щастлив.“ – Стругацкие, А. и Б. Жук в муравейнике, Серия „Лучшие книги братьев Стругацких“, Москва: „Издательство АСТ“, 2023, с. 87. Курортът в Бръмбар в мравуняка носи тривиално-фолклорното сладникаво-умалително наименование „Трепетличката“ (Осинушка). Ще се спра по-нататък отделно на синоптичното четене на Бръмбар в мравуняка и Сталкер.

Тази хроника на създаването на Сталкер е компилирана от Цымбал, Е. Рождение «Сталкера». Попытка реконструкции, Москва: «Новое литературное обозрение», 2022, най-пълното и първоличностно-свидетелски достоверно изследване на предмета, написано от участник в снимачната работа – един от малкото все още живи.

списание „Нова социална поезия“, юни 2024, ISSN 2603-543X