Art reflects reality through the artist’s point of view and perspective. Art, however, does not imitate nature and real life, but instead, it depicts the artist’s feelings, imagination and attitude towards nature and real life. Throughout the ages, though, art had different roles, such as a religious role. In Ancient Greece, for example, art was admired for its aesthetic qualities, but at the same time artworks majorly depicted mythological scenes, making them religious objects as well. The case during the Medieval Ages in Europe was similar. Since a major part of the people during that age were illiterate, they could not possibly learn about Christianity through books. Art was serving an educational role, making religion accessible for the mass. However, famous artworks were mainly in the possession of the wealthy, or in the people of control. This phenomenon continued after the Medieval Ages, making fine art a bourgeoise pleasure. Art was taken away from the common people since they were thought to not be educated enough and thus not able to appreciate art as such. The working-class had not had art targeting them. Even if the artwork depicted working-class or agricultural scenes, it was again bourgeoise art. The Church during Medieval Ages treated art as something available for the masses, but this availability aimed to maintain control over people using religion. If people do not have constant access to religion through various media, this would jeopardize the Church’s position in society. After abolishing Christianity’s control over society „for the sake of the people“, ironically, art become unavailable. I believe art is important to the cultural health of a society, just like food and water are important for the physical health, and a society without available art suffers from cultural sickness. The workers, and overall, the people who do not belong in the ruling or the bourgeoisie class are being underestimated and derogated by being thought they are not capable of simply enjoying art. Moreover, during the Dutch Golden Age, for example, art was mainly depicting the wealth of the Netherlands and its conquering achievements. Even still-life paintings showed the viewer only the most expensive commodities. This was, in a way, bourgeoise propaganda that showed the Netherlands in its brightest side, almost completely forgetting about the lower class of people. However, various artists from the 19th and 20th century used art’s impacting and engaging qualities to spread their ideologies. This essay will discuss the question of whether art can be used as a weapon of political activism or resistance. I will discuss the matter in relation to Mexican Muralism, specifically Diego Rivera’s art.

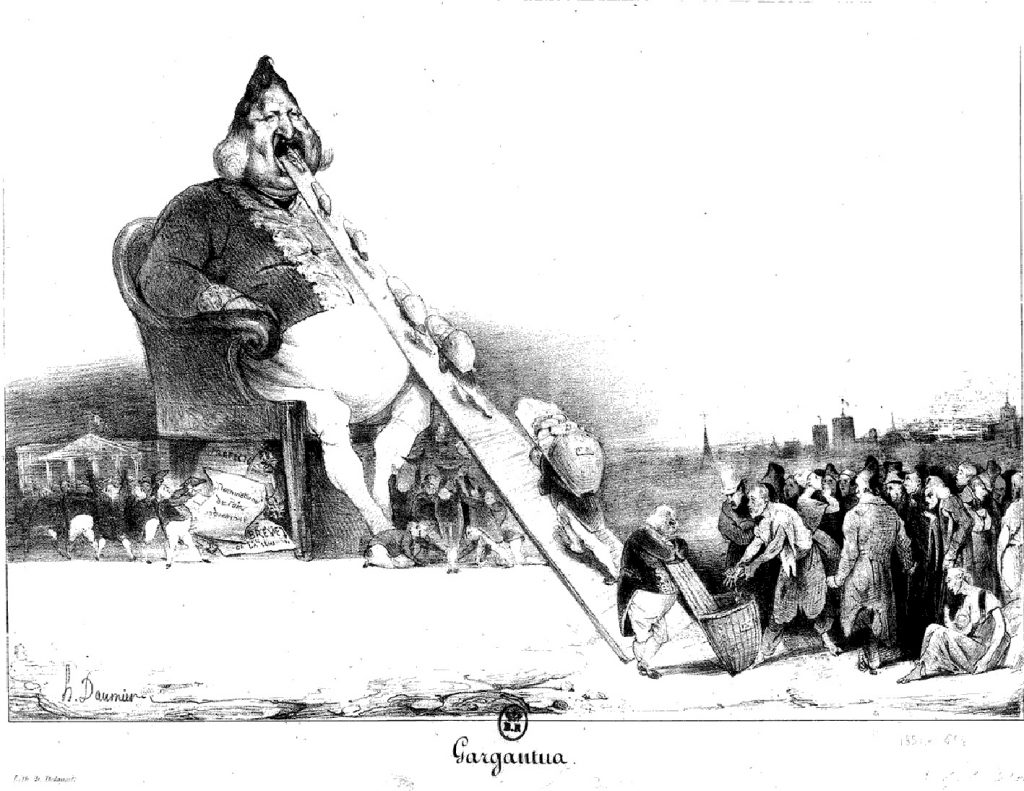

In the 19th century, there were artists that started to stress on the working-class’ struggle and issues. Such artists are Honoré Daumier, Gustave Courbet, and later Van Gogh, for example. Daumier, despite himself being a bourgeois, had focused on paintings which showed the workers, or paintings which parody the bourgeoisie. One of his major and famous caricatures with a political message against the rulers and the wealthy is Gargantua (Figure 1) painted in 1831. In the artwork, we see King Louis-Philippe, who was the ruler of France at the time Daumier was an active artist. The ruler’s head was drawn in the form of a pear, which was a common form of depiction of the king in Daumier’s art. There is a stepping board which leads to the king’s mouth, and on that board, we can see the king’s servants carrying sacks of money which end up in the ruler’s mouth. The money is gathered from the taxpayers which are depicted on the left, emptying their pockets and giving their money to the servants. This is a straightforward depiction of the monarch’s ruling methods, meaning that he makes wealth off the common folk’s labour. Daumier perfectly shows how cruel was the exploitation of the working-class, and how the ruler was the only one benefiting from this situation. The way the people who give their money to the king are depicted in the picture – the woman with a child in the bottom right, for example – show us how unfair is the king’s ruling is to the people. Gargantua has a message that could make the viewer actually think about the unjust situation in France, and not only admire the artwork for its aesthetic values. Daumier emphasizes on the message and social awareness in some of his paintings, rather than on the aesthetic quality of his art. Namely this fact, I suppose, made Diego Rivera look into Daumier’s art and discuss it briefly in his The Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art. Rivera says that Daumier definitely produced revolutionary art, without actually painting in a revolutionary character. Daumier’s art was not actual leftist propaganda, but, as Rivera notes, the viewer can see that he depicted the world through his „class-conscious“ eye. Diego Rivera says that there is no need for one to be from the working-class in order to realize its problems, and give voice to them. Daumier used art to reach the people.His class-conscious artworks were not suitable for installing in a palace, or in a bourgeois mansion, but were meant for the mass. His art was not „pure art“ of which critics like Greenberg talk and praise. Daumier’s art was meant not only to be enjoyed but also to be understood and to be used as a tool for the awakening of the working-class. That type of art can be considered as peaceful activism, since it does not promote violence against the rulers, but makes the viewers realise their situation.

As we can tell by Rivera’s The Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art, artists like Daumier played a major role in influencing Rivera’s own art. Rivera said „Every strong artist has been a propagandist. I want to be a propagandist and I want to be nothing else. I want to be a propagandist of Communism… I want to use art as my weapon.“ He simply says that bourgeois „art for art’s sake“ or „pure art“ is not as valuable as activist and propaganda art since it cannot be used as a weapon. Rivera wants to use art to reach the people and spread his leftist political views. Such art is also a form of resistance against conservatism and right-wing ideas as a whole. Rivera sees art as the easiest and most accessible way to promote ideas. Art is probably the most impacting form of message since it can be both entertaining and educational and it can be straightforward as well. All these characteristics are combined in the muralist movement in Mexico, occurring in 1920-1940. Diego Rivera is one of the leaders of this movement, along with José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Muralists wanted their art to be as reachable as possible, that is why they installed it in public places. They did not want their art to be sophisticated and private and perhaps did not want to make a profit out of it. On one hand, muralists wanted people to have bigger access to art, since until then art was meant only for a small group of people and it was not fair to the mass of people who were not wealthy enough to afford artworks, and/or were not born in high-class families, whose members are thought to possess an inborn ability to appreciate art. On the other hand, muralists wanted to spread their political views as wider as possible and wanted everyone to be educated about Communism. Let us imagine that the muralists, instead of painting frescoes publicly, gave away copies of the Communist Manifesto. Part of the people may actually take the book, read it and become affected by it, but the chance is that most of the people would not engage with the Manifesto in a proper way, since it is not as reachable as art. Although activist and propaganda art may not be as detailed, concrete and exhaustive as a theoretical work like the Manifesto, it has a wider reach and bigger impact on the masses as a whole and may even make people more interested in further education on the matter. Muralists knew this and chose to use their talent as the weapon of their propaganda. Public art is a fast, easy and a rather successful way of spreading an idea. The muralists also wanted to show people that they are on their side as part of their propaganda. With muralism, those artists wanted to show to the people an image of modernized Mexico. In their art they mixed European aesthetics with local culture and traditions, making their art both admirable and comfortable. Diego Rivera held the believe that art is as important to one’s health as it is food and water. The latter keeps the body in a healthy condition, while the former is important for one’s psyche and soul. Without access to art, the mass is spiritually crippled and their lust for life is fading.

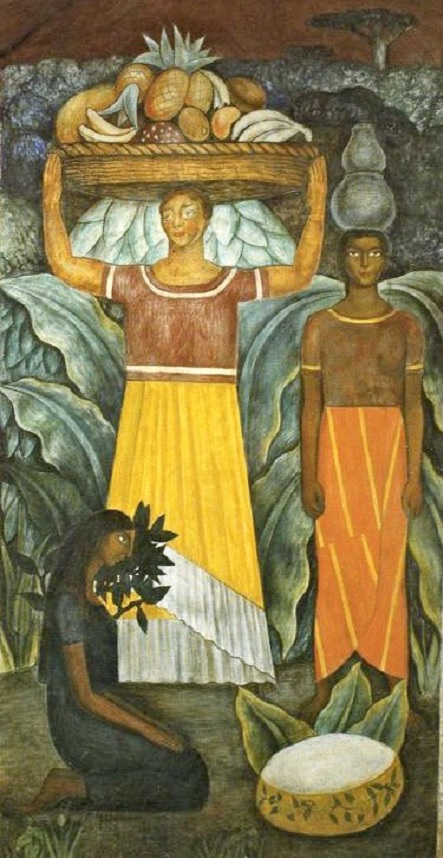

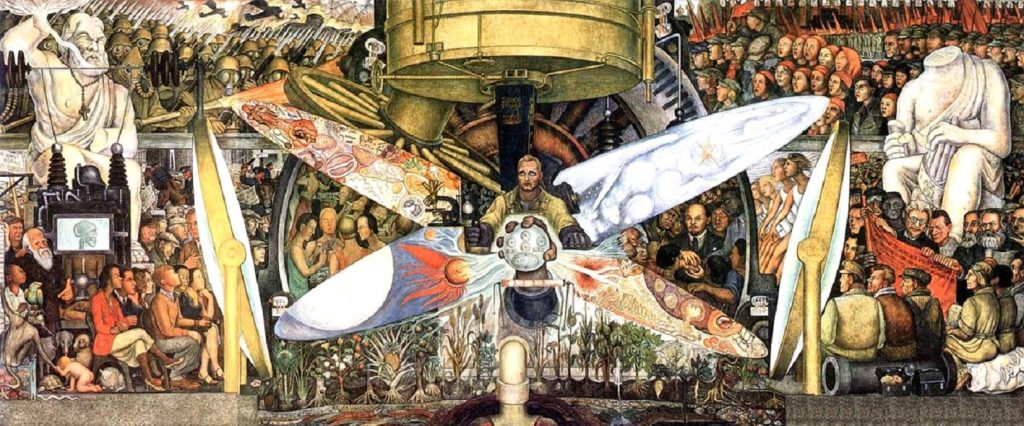

In his artworks, Rivera wanted to show the rise of the proletariat and the workers’ triumph. One of the most important murals regarding this topic is the vast mural cycle he painted in the national Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City between 1923 and 1929. In the mural cycle, Rivera wanted to show the evolution that indigenous people of Mexico would go under after education, industrialisation, and most importantly, revolution. The paintings show the transformation of labour and lifestyle after certain political changes in Mexico. With this mural cycle, Diego Rivera spreads the message of the positive outcome from a leftist revolution. The paintings show how the people will no longer be oppressed and that Rivera and other Mexican communists’ ideas are in favour of the people. The mural’s main message is shown in two parts, named by the artist as the Courtyard of Labour and the Courtyard of Fiestas. Metaphorically, the former is executed in the first floor of the building, while the latter is painted in the second floor. Here, Rivera uses architecture as a metaphor for the people’s rise. On the first level, we see traditional practices of production like weaving, depicted next to other forms of labour like mining. In this panel, there’s a painting called Tehuanas (Figure 2), in which we see a woman bearing a basket of fruit on her head, another woman by her side which also carries fruit on her head, and a kneeling woman in front of them. This painting shows the indigenous people’s everyday life and traditions. In the Courtyard of Labour, we see various scenes of indigenous Mexican traditions – festivals, dances etc. Ascending to the third level of the Courtyard of Fiestas, we see a painting called Our Bread (Figure 3) that represents the triumph of the proletariat. In Our Bread we see the woman from Tehuanas who was carrying a basket of fruit on her head standing in front of a table. Behind her, we can see clear skies, which is a utopian metaphor of triumph and prosperity. Next to her, we see what might be a military general or a soldier, who, now that the proletariat have prevailed, is free to join the celebration. Behind the woman, we see men with traditional Mexican hats, who are probably workers. In front of her, we see a table, and in the central seat there is a man who is breaking a loaf of bread. On the chairs around the table, there are various people, men and women, from different age groups. They are waiting for the man to give away the bread. The painting shows that after the proletariat’s victory there will be no restrictions regarding age, gender or ethnicity. Everybody is welcomed in the Communist classless society, and namely this is what Rivera wants to show in this painting. The proletariat’s triumph will lead to harmony. Our Bread also shows the Tehuana’s rise. In Tehuanas she seems isolated, while in Our Bread she has joined the celebration and the careless, utopian life. Thus, the mural’s name – Courtyard of Fiestas. On the same floor as the Courtyard of Fiestas, we see the painting Wall Street Banquet (Figure 4), painted in 1928. It uses a similar model to Our Bread, and just like it, it can be considered as both political resistance and activism. But, while Our Bread shows us the positive outcomes of a Communist revolution, Wall Street Banquet criticises the enemies of this ideology. Again, the painting depicts people sitting around a table. In the centre of the painting, though, it was not depicted a person, but a vault. This shows us that the people in the painting value wealth more than humans, and the centre of their lives is money. We do not see any food on the table. Eating with someone is a sign of warmth and propinquity. Usually families and close friends eat together, and in Our Bread, the idea is that everyone in the classless society will be part of one big family. The case of Wall Street Banquet is different. There is champagne on the table, which is a sign of wealth rather than of closeness and warmth. The people in the painting are gathered by business interests rather than sympathy. Everyone’s facial expression is rather cold and evil, unlike the people in Our Bread which look calm and happy. The capitalists in Wall Street Banquet are too serious and too busy to be happy and one can assume that they do not enjoy each other’s company. They read a golden ticket tape, but we can see that only the men in the painting have access to it. This also tells us about the patriarchy and sexism of the Western capitalist world. The woman on the nearest left seems more like holding the tape, rather than reading it. Another juxtaposition between Our Bread and Wall Street Banquet is that there are no children in the latter. In the cold capitalist world, there is no place for children and their joy and carelessness. Among the people depicted in Wall Street Banquet are John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, and J.P. Morgan. Ironically, Rivera was invited by Rockefeller to execute a mural piece in his tower. In 1934 the artist executed Man at the Crossroads (Figure 5) for Rockefeller, which was destroyed afterward because of the Communist message in it. The murals from the Courtyard of Labour and the Courtyard of Fiestas are included in the ballet H.P., composed by the Mexican composer Carlos Chávez in 1926-32.

By the time muralism was prospering and Diego Rivera was already a significant artist in Mexico, in Europe Modernism and Formalism were the established artistic movements. Modernism was very critical of paintings with political messages and Formalism focused on the paintings’ forms, lines, and flatness, rather than the story and message behind them. Thinkers like Clement Greenberg and Roger Fry had noted in their works that message in paintings was irrelevant and useless. In a 1969 interview, Greenberg said that art „solved nothing, either for the artist himself or for those who receive his art“. For Greenberg, political art was „poor art for poor people“. In his work Modernist Painting, he stated that message and story belonged to literature, and in Modernist paintings all the elements taken from other types of art should be excluded, since they concealed art’s quality and purpose. Greenberg also said that the artist’s role was to make good art, and social awareness had not helped in the making of good art. The Modernist movement thought that the artists did not have the right to raise social awareness and that art had to be apolitical. Roger Fry also admitted that art’s main qualities come from „pure form“. Pure form produces a unique aesthetic feeling in the viewer, and other feelings that come from the artist’s background, or from the artwork’s theme and concept were secondary or irrelevant. Rivera completely disagreed with those statements and thought that a powerful artist necessarily needs to be part of the contemporary social struggle of his time and needs to raise awareness with his art. Ironically, Rivera adopted European Modernist art in his artworks, which was moved namely by Formalism and Modernism.

Rivera managed to use art as a weapon and a tool for the spreading and amplification of the Communist ideology. He thought that the most viable way to be heard is through art since it is straightforward, reachable and amusing at the same time. Moreover, he painted his artworks in public spaces, making his art and his message even more available to the people. His art was influenced by the leftist movement and spread propaganda about the people’s prosperity and well-being after an eventual Communist revolution. Art, as he proved, can be considered as both forms of political activism and political resistance. However, the times during which Rivera was active were critical of such art, and Rivera was not critically acclaimed by the European standards of Modernist art. Rivera was not concerned about this fact and kept filling his art with messages about social awareness and class struggle. His art was a manifestation of the working-class’ issues and at the same time possessed certain, unique aesthetic qualities, which was the result of combining European Modernist style with traditional Mexican culture.

Bibliography:

Belnap, Jeffrey. „Diego Rivera’s Greater America Pan-American Patronage, Indigenism, and H.P.“ Cultural Critique, no. 63 (2006): 61-98.

Ferrari, Marry A.. The Use of Path Dependence to Explain the Representations of United States Industrialism in Mexico in Diego Rivera’s Murals. The Pennsylvania State University, Schreyer Honors College, 2015

Greenberg, Clement. “Modernist Painting”, 1965, in Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison (eds.), Modern Art and Modernism. A Critical Anthology, London, 1982

Rivera, Diego. “The Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art.” The Modern Quarterly Vol. 6, No. 3. Baltimore: Autumn 1932: 51-57. Reproduced in Anreus et al, Mexican Muralism. 322-330

Wolf, Virginia. Roger Fry, A Biography. London, 1940

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

списание „Нова социална поезия“, бр. 28, май, 2021, ISSN 2603-543X